I wrote 1,300 words of novel on Saturday and 2,300 words yesterday before 3.30 p.m. This constituted an enormous effort. At 10 p.m. we went on to a rehearsal of "The Miracle" at the Residenz. Reinhardt left at 10.45 to go to an 11 p.m. dinner at Leopoldskron. Whereupon Rosamund Pinchot (the Nun) had an attack of nerves because he wasn't there to direct her, and her mother was upset. I told her it was the most ordinary thing in the world and not worth thinking about.

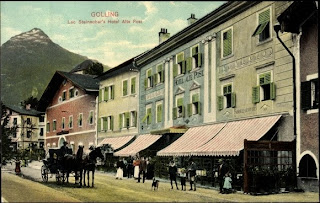

See also, 'Sightseeing from Salzburg' - August 2nd.,

http://earnoldbennett.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/sightseeing-from-salzburg.html

Max Reinhardt (1873 – 1943) was an Austrian-born American stage and film actor and director. Born Maximilian Goldmann, an Austrian Jew, from 1902 until the beginning of Nazi rule in 1933, he worked as a director at various theatres in Berlin. From 1905 to 1930 he managed the Deutsches Theatre ("German Theatre") in Berlin. By employing powerful staging techniques, and harmonising stage design, language, music and choreography, Reinhardt introduced new dimensions into German theatre. After the Anschluss of Austria to Nazi-governed Germany in 1938, he emigrated first to Britain, then to the United States. Reinhardt opened the Reinhardt School of the Theatre in Hollywood, on Sunset Boulevard. In 1940 he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

I only had three and three-quarter hours sleep on Saturday night, and yet wrote 2,300 on Sunday.

At 4 p.m. took the railway up to the summit of the Gaisberg. Too misty and sunshiny to see clearly but it was all very impressive. A damn fine lump of mud, the Gaisberg, 4,200 feet.

Kommer gave a 2.15 p.m. lunch, at which we met Hugo von Hoffmansthal and wife. He is a very jolly fellow, about 45 I should say, and looking younger. Three children practically grown up, I understood. Just bought his first car, of which he was most naively and charmingly proud. he said that of course I, being a novelist, wrote all the year round and that he, being a dramatist, worked only in the autumn. I was delighted with H. von H.; also with his wife.

Hugo Laurenz August Hofmann von Hofmannsthal (1874 – 1929), was an Austrian novelist, librettist, poet,dramatist, narrator, and essayist. He began to write poems and plays from an early age. In 1900, Hofmannsthal met the composer Richard Strauss for the first time and later wrote libretti for several of his operas. In 1901, he married Gertrud "Gerty" Schlesinger, the daughter of a Viennese banker. Gerty, who was Jewish, converted to Christianity before their marriage. They settled in Rodaun, not far from Vienna, and had three children, Christiane, Franz, and Raimund. During the First World War Hofmannsthal held a government post. He wrote speeches and articles supporting the war effort, and emphasizing the cultural tradition of Austria-Hungary. The end of the war spelled the end of the old monarchy in Austria; this was a blow from which the patriotic and conservative-minded Hofmannsthal never fully recovered. Nevertheless the years after the war were very productive ones for him; he continued with his earlier literary projects, almost without a break. In 1920, Hofmannsthal, along with Max Reinhardt, founded the Salzburg Festival. On July 13, 1929, his son Franz committed suicide. Two days later, Hugo himself died of a stroke at Rodaun. He was buried wearing the habit of a Franciscan tertiary, as he had requested.

Hugo Laurenz August Hofmann von Hofmannsthal (1874 – 1929), was an Austrian novelist, librettist, poet,dramatist, narrator, and essayist. He began to write poems and plays from an early age. In 1900, Hofmannsthal met the composer Richard Strauss for the first time and later wrote libretti for several of his operas. In 1901, he married Gertrud "Gerty" Schlesinger, the daughter of a Viennese banker. Gerty, who was Jewish, converted to Christianity before their marriage. They settled in Rodaun, not far from Vienna, and had three children, Christiane, Franz, and Raimund. During the First World War Hofmannsthal held a government post. He wrote speeches and articles supporting the war effort, and emphasizing the cultural tradition of Austria-Hungary. The end of the war spelled the end of the old monarchy in Austria; this was a blow from which the patriotic and conservative-minded Hofmannsthal never fully recovered. Nevertheless the years after the war were very productive ones for him; he continued with his earlier literary projects, almost without a break. In 1920, Hofmannsthal, along with Max Reinhardt, founded the Salzburg Festival. On July 13, 1929, his son Franz committed suicide. Two days later, Hugo himself died of a stroke at Rodaun. He was buried wearing the habit of a Franciscan tertiary, as he had requested.This is the third day of very hot stifling weather, with sun all the time.

Leave tomorrow, Tuesday, 11th., at 5.30, by the Orient Express. I shall have been here 33 full days, and I estimate I have written over 35,000 words despite chronic and acute neuralgia.