On Friday I was still suffering so much from the effects of neuralgia that I could do no work. Shopped in the afternoon, and went to see a German film in the evening; it was very bad, as bad as the weather. Yesterday also I was suffering, and so I decided to go out for the day.

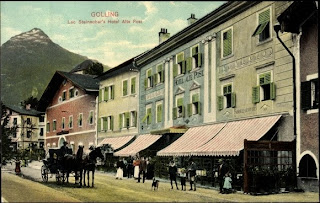

Through Hallein to Golling, a large village full of medium hotels. Lunch at the Alte Post, whose proprietor, Steinach, told me that the hotel had been in the hands of his family for 111 years. Began lunch with the largest trout I have ever seen - caught two hours earlier. Golling and other villages near have a character of their own. The gables of the houses face the street; wide eaves, sometimes a balcony under the eaves with a tiled roof of its own. brightly painted window frames and shutters, and plenty of flowers on the sills. Plenty of visitors. At the Alte Post were four rooms fairly full of lunchers; we lunched on the terrasse.

After lunch took a two-horse carriage to see the waterfalls. The car couldn't go, because the bridge over the Salzach is forbidden to cars. About 10 minutes drive, and then about 50 minutes to climb steps and things in order to see the three waterfalls, one above another. The waterfalls were fully up to descriptions thereof and really most impressive. I have never seen anything to beat this drive for grandeur of scenery. At Werfel we stopped at 4 p.m. for coffee at an outwardly unassuming hotel and had superb coffee and cakes, very well served by a smart, slim, sparkling waitress. Within I saw the kitchen and a chef in a chef's white cap making pastry. It was strange to see this perfection in a village lost in the mountains.

On the way home, between Hallern and Salzburg, we came upon a motor accident, collision; the road was unnecessarily blocked for a long time during palavers between the respective owners and drivers and the gendarme. The chief words repeated 1,000 times, were "mein lieber herr". Everybody nervously excited but very polite and restrained.

After dinner Kommer came along to the hotel with Rosamund Pinchot and two German journalists. He introduced Rosamund. A day or two ago he had told me the astounding story of how Reinhardt had seen this society girl on the tender, going to America, and had instantly said: "Here is the girl who can play the nun" ("The Miracle"), and had ultimately engaged her, though she had no experience whatever of the stage, nor any longing to go on the stage.

In 1923, Rosamond Pinchot was a 19-year-old with lots of opportunities in life. Tall and golden-haired, she lived in a townhouse on East 81st Street and attended exclusive Miss Chapin’s School. Then, on a ship, she had a fateful encounter. She was returning to New York from a trip to Europe with her mother when theatre bigwig Max Reinhardt spotted her. Reinhardt wanted her as the lead in a play he would be directing on Broadway, The Miracle, about a nun who leaves her convent. With no dramatic experience, she accepted the offer, skipping her official debut into society in favour of the stage. Later that year, the play opened at the Century Theatre on Central Park West. Rosamond blew everyone away. Dubbed the “loveliest woman in America,” Rosamond became an It Girl of the 1920s and the toast of Hollywood. She played the part for three years and took roles in other productions, until 1926, when she quit acting to do “serious” work. She tried her hand at a variety of things: She studied history in college, sold real estate, then returned to the stage several times and made her only film appearance in 1935′s The Three Musketeers. She also got married in 1928 to the grandson of a former Massachusetts governor and had two sons. The marriage didn’t last—and her separation from her husband in 1936 “deeply affected” her. Rosamond made her last theatrical appearance in 1937. The next year, at age 33, she committed suicide by poisoning herself with carbon monoxide in her garage on her estate in Long Island. A note was left behind, but the contents were never divulged.

I finished "The Kellys and the O'Kellys" yesterday morning: Trollope's second novel, written at the age of 34. This novel is consistently excellent, and Algar Thorold's introduction to it is absurdly trifling and inadequate. The characterisation is admirable, strong, true, and sober.

No comments:

Post a Comment