Thursday, March 12th., Les Sablons.

I have tried for two days to find the rhythms for two poems that I found ideas for - one elegiac and the other Aristophanic, and can't. I am starting to feel, but perhaps not yet quite accepting, that poetry is not my medium. There is a sort of disconnection between my original conception and what appears when I write. Of course there are not many writers who have equal facility at poetry and prose. Hardy springs to mind, and Kipling. I may be wasting my time. When I have shown poems to a select few friends they are kind of course, but hardly enthused. Time to focus on what I can do well!

Speaking of which, I have read through the first part of "Old Wives Tale", and am deeply persuaded of its excellence. Also I feel ready to make a start on the second part on Saturday. The ideas have come quite easily. I am looking forward to getting on.

Today I had a notion for a more or less regular column of literary notes - title 'Books and Persons' - for the New Age, and I wrote and sent off the first column at once. I began to work this morning in bed at 6 a.m.

Yesterday I cycled in showers and through mud to Fontainebleau to meet the architect at the new house. Found it damp, but the works more advanced than I had expected.

Been reading Lord Acton. I am driven to the conclusion that his essays are too learned in their allusiveness for the plain man. I should say that for a man who specialised in the history of the world during the last 2,500 years they would make quite first class reading. I am not that man.

Welcome to our blog!

It's better than a bat in the eye with a burnt stick!

This blog makes liberal use of AB's journals, letters, travel notes, and other sources.

And make sure to visit The Arnold Bennett Society for expert information and comment on all aspects of the life and work of AB.

Showing posts with label Kipling. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Kipling. Show all posts

Monday, 12 March 2018

Thursday, 4 January 2018

Writers

Tuesday, January 4th., Royal York Hotel, Brighton.

When I came downstairs this morning full to the brim with the first chapters of "Clayhanger", I found a letter from Herbert Trench asking me to alter tremendously the third act of "The Honeymoon". My soul revolted, but of course I gradually gave way and then wrote him that I would.

I was occupied with letters till 11, and then I went out to recover myself for "Clayhanger" and I did so. The recuperative power of sea air. I worked till 1 0'clock and again after lunch, and again after dinner. So that now I have got the opening of the book pretty ripe.

This afternoon we went to have tea with the Sidney Lows at the Metropole. Low told me how he discovered Kipling, and how his superiors on the Indian daily didn't think anything of him at all, but Low insisted on getting hold of his stuff. It seems he was very shy and young at the start. Low also insisted on Hall Caine's powers as a raconteur, as proved at Cairo when he kept a dinner party of casual strangers interested for an hour and a half by a full account of the secret history of the Druce case, which secret history he admitted afterwards was a sheer novelist's invention.

This afternoon we went to have tea with the Sidney Lows at the Metropole. Low told me how he discovered Kipling, and how his superiors on the Indian daily didn't think anything of him at all, but Low insisted on getting hold of his stuff. It seems he was very shy and young at the start. Low also insisted on Hall Caine's powers as a raconteur, as proved at Cairo when he kept a dinner party of casual strangers interested for an hour and a half by a full account of the secret history of the Druce case, which secret history he admitted afterwards was a sheer novelist's invention.

When Caine was with Low in Egypt he saw everything as a background to "The White Prophet", which was originally meant as a play for Tree. When Low showed him the famous staircases in the Ghezireh Palace he said, "I can get three different entrances underneath that". And when he saw the pyramids, he said, "Tree can do simply anything with those". The Sidney Lows said he was the kindest, nicest sort of man in private life (but Low told me behind his hand that he was also apt to be tedious on the subject of himself, and naif). Present also, inter alia, the wife of T.H.S. Escott, who lives at Brighton but is paralysed. He still works and produces however, and has a new book just coming out.

When I came downstairs this morning full to the brim with the first chapters of "Clayhanger", I found a letter from Herbert Trench asking me to alter tremendously the third act of "The Honeymoon". My soul revolted, but of course I gradually gave way and then wrote him that I would.

I was occupied with letters till 11, and then I went out to recover myself for "Clayhanger" and I did so. The recuperative power of sea air. I worked till 1 0'clock and again after lunch, and again after dinner. So that now I have got the opening of the book pretty ripe.

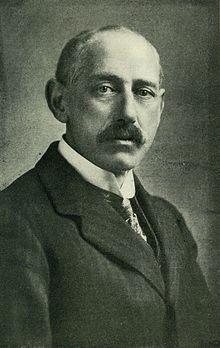

|

| Sir Sidney Low |

This afternoon we went to have tea with the Sidney Lows at the Metropole. Low told me how he discovered Kipling, and how his superiors on the Indian daily didn't think anything of him at all, but Low insisted on getting hold of his stuff. It seems he was very shy and young at the start. Low also insisted on Hall Caine's powers as a raconteur, as proved at Cairo when he kept a dinner party of casual strangers interested for an hour and a half by a full account of the secret history of the Druce case, which secret history he admitted afterwards was a sheer novelist's invention.

This afternoon we went to have tea with the Sidney Lows at the Metropole. Low told me how he discovered Kipling, and how his superiors on the Indian daily didn't think anything of him at all, but Low insisted on getting hold of his stuff. It seems he was very shy and young at the start. Low also insisted on Hall Caine's powers as a raconteur, as proved at Cairo when he kept a dinner party of casual strangers interested for an hour and a half by a full account of the secret history of the Druce case, which secret history he admitted afterwards was a sheer novelist's invention.When Caine was with Low in Egypt he saw everything as a background to "The White Prophet", which was originally meant as a play for Tree. When Low showed him the famous staircases in the Ghezireh Palace he said, "I can get three different entrances underneath that". And when he saw the pyramids, he said, "Tree can do simply anything with those". The Sidney Lows said he was the kindest, nicest sort of man in private life (but Low told me behind his hand that he was also apt to be tedious on the subject of himself, and naif). Present also, inter alia, the wife of T.H.S. Escott, who lives at Brighton but is paralysed. He still works and produces however, and has a new book just coming out.

Thursday, 20 September 2012

Literary thoughts

Wednesday, September 20th., Les Nefliers

I have been re-reading Kipling, and thought "Without Benefit of Clergy" fine, and yet perhaps not great. Other things pretty good but certainly not great.

Also William Watson, as to whom I am obliged to revise my estimate. If he isn't sometimes a great poet he comes near to being one.

And now I am re-reading "Wilhelm Meister" after about twenty years.

I have been re-reading Kipling, and thought "Without Benefit of Clergy" fine, and yet perhaps not great. Other things pretty good but certainly not great.

This story first appeared in Macmillan’s Magazine for June 1890 and in Harper’s Weekly on 7 and 14 June the same year.In it John Holden leads a double life. To his colleagues in the civil service he is a bachelor, living in spartan bachelor quarters, and sometimes neglecting his work. But he has set up a young Muslim girl, Ameera, in a little house on the edge of the old city. She is the love of his life, and he of hers. They are idyllically happy together, and when she gives birth to a baby boy, Tota, their happiness is complete. When Tota dies of fever, they are distraught. Then Ameera is stricken with cholera and dies in Holden's arms. He is left desolate, and the house is soon pulled down. The idyll is over as if it had never been.

By strict definition, 'Benefit of Clergy' was the right of exemption from trial in a secular court by those in Holy Orders: which later included all who could read. (This was abolished by 1841). However, Kipling’s punning use of the expression hinges on the fact that Holden and Ameera are living as man and wife without the blessing of his Church or hers; had one of them converted, they might have married, but such a union would have meant both social and professional ruin for Holden.

Sir William Watson (2 August 1858 – 13 August 1935), was an English poet, popular in his time for the political content of his verse. He was born in Burley, in West Yorkshire. He was a prolific poet of the 1890s, and a contributor to The Yellow Book, though without 'decadent' associations. Indeed he was very much on the traditionalist wing of English poetry. He had a gift for resonant phrasing and reiterative rhythms which he mistook (and for 20 years many critics mistook) as a gift for poetry.

And now I am re-reading "Wilhelm Meister" after about twenty years.

Everybody has heard of Goethe, but the English have always had a tricky relationship with him. AS Byatt puts it perfectly: "Little of his major work resembles the forms and values we are comfortable with in our own literatures." That's why I like him. The hero of Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship dreams of a life in the theatre, as exotic to him as space travel might seem to us. When an actress breaks his heart, he sets off with a touring company, encountering strange characters such as Mignon, an androgynous child, and a gloomy harp-playing minstrel whose songs Schubert set so beautifully. Goethe's writing is simple, elegant and uncluttered; the naturalism lures us into a story that gets odder by the page. Coincidences mount; there's a book-within-the-book that seems a complete digression. Then we find ourselves back with Wilhelm, at a mysterious castle where he meets members of the secret Society of the Tower, who have been conducting events all along. Everything connects; Wilhelm's life is a scroll in their library.

We can see what Byatt meant: this is strange stuff, and one writer hugely influenced by it, surely, was Franz Kafka. So were Walter Scott, James Hogg and Thomas Carlyle: Goethe's sense of the uncanny found a receptive audience in 19th-century Scotland.

The lesson of the book is that we should give unity to our lives by devoting them with hearty enthusiasm to some pursuit, and that the pursuit is assigned to us by Nature through the capacities she has given us. Sir J. R.Seeley

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)