Monday, December 19th., Rue de Calais, Paris.

I sent off the last act of "An Angel Unawares" yesterday morning. In the afternoon I went to have tea with Miss Thomasson. I find that she is disturbing me, so much so that today I could not settle to anything definite. There is an element of sexual frustration in this.

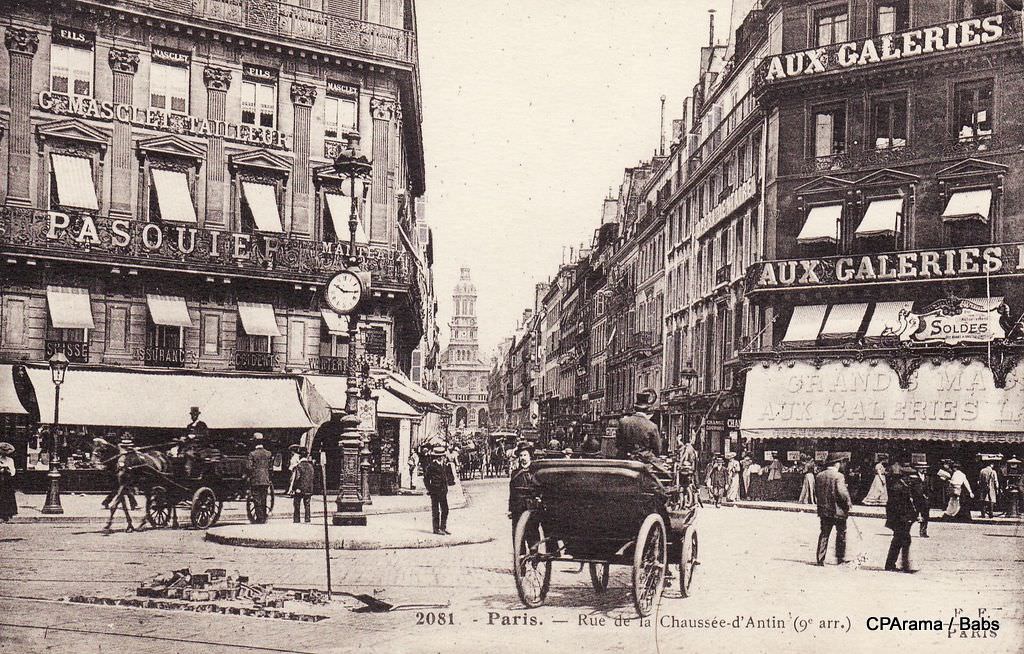

So, this evening I had to go out and walk about. Perhaps I was looking for an 'adventure'? I turned down the steep Rue Blanche and at the foot of it passed by the shadow of the Trinite, the great church of illicit assignations, at whose clock scores of frightened and expectant hearts gaze anxiously every afternnoon. And through the Rue de la Chausee d'Antin, where corsets are masterpieces beyond price and flowers may be sold for a sovereign apiece. Then into the full fever of the grand boulevard with iots maddening restlessness of illuminated signs. This was the city. This was what the race had accomplished after eighteen Louis' and nearly as many revolutions, and when all was said that could be said it remained a prodigious and comforting spectacle. Every doorway shone with invitation; every satisfaction and delight was offered, on terms ridiculously reasonable. So different it seemed from the harsh and awkward timidity, the self-centred egotism and aristocratic hypocrisy of Piccadilly.It seemed strange to be lonely amid multitudes that so candidly accepted human nature as human nature is. Sex was in the air, but I could not grasp it.

So I continued southwards, down the narrow, swarming Rue Richelieu, past the National Library on the left and the Theatre Francais, where nice plain ppeople were waiting to see "L'Aventuriere", and across the arcaded Rue de Rivoli. And then I was in the dark desert of the Place du Carrousel, where the omnibuses are diminished to toy-omnibuses. The wind, heralding winter, blew coldly across the spaces. The artfully arranged vista of the Champs Elysee, rising in flame against the silhouette of Cleopatra's Needle, struck me as a meretricious device, designed to impress tourists and monarchs. Everything seemed meretricious. I could not even strike a match without being reminded that a contented and corrupt inefficiency was corroding this race like a disease. I could not light my cigarette because somebody, somewhere, had not done his job like an honest man.

I wanted to dine but all the restaurants had ceased to invite me. I was beaten down by the overwhelming sadness of one who for the time being has no definite arranged claim to any friendly attention in a huge city. I might have been George Gissing. I re-wrote all his novels for him in an instant! I persisted southwards. The tiny walled river, reflecting with industrious precision surrounding lights, had no attraction, except as a potential solution. The quays where all the bookshops were closed and all the bookstalls locked down, and where there was never a cafe, were as inhospitable and chill as Riga. Mist seemed to heave over the river, and the pavements were oozing with damp. I turned for home.

To think that in three days I shall be in Burslem!

No comments:

Post a Comment