Illustration of the sans-gene of Montmartre. As I was sitting on the terrace of the Cafe de la Place Blanche, a voiture drove up containing two men, two women and a white puppy. One of the men was clearly an actor or singer of some sort, he had the face and especially the mouth; one of the women, aged perhaps 25, short, getting plump, and dressed with a certain rough style, especially as to the chic hat and the jupon, was evidently his petite amie; the other woman was a servant, nu-tete and wearing a white apron; the other man had no striking characteristic. The two men and the petitie amie got out and sat near me. the driver turned away.

|

| La Place Blanche 1911 |

Afterwards I dined with the Schwobs.

Marcel Schwob was born in Chaville, Hauts-de-Seine on 23 August 1867. He studied Gothic grammar under Ferdinand de Saussure at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in 1893-4, and later earned a doctorate in classic philology and oriental languages. In 1884 he discovered Robert Louis Stevenson, who became one of his models, and whom he translated into French. He was a true symbolist, with a diverse and an innovatory style. He is the author of six collections of short stories: Cœur double ("Double Heart", 1891), Le Roi au masque d’or ("The King in the Golden Mask", 1892), Mimes(1893), Le Livre de Monelle ("The Book of Monelle", 1894), La Croisade des Enfants ("The Children's Crusade", 1896), and Vies imaginaires ("Imaginary Lives", 1896). Alfred Vallette, director of the leading young review, the Mercure de France, thought he was "one of the keenest minds of our time", in 1892. Marcel Schwob worked on Oscar Wilde's play Salome, which was written in French to avoid a British law forbidding the depiction of Bible characters on stage. Wilde struggled with his French, and the play was proof-read and corrected by Marcel Schwob for its first performance, in Paris in 1896. His work pictures the Greco-Latin culture and the most scandalous characteristics of the romantic period. His stories catch the macabre, sadistic and the terrifying aspects in human beings and life. He became sick in 1894 with a chronic incurable intestinal disorder. He also suffered from recurring illnesses that were generally diagnosed as influenza or pneumonia and received intestinal surgery several times. In the last ten years of his life he seemed to have aged prematurely. In 1900, in England, he married the actress Marguerite Moreno, whom he had met in 1895. His health was rapidly deteriorating, and in 1901 he travelled to Samoa, like his hero Stevenson, in search of a cure. On his return to Paris he lived the life of a recluse until his death in 1905. He died of pneumonia while his wife was away on tour.

First night of Jean Aicard's drama in verse, "La Legende du Coeur", at the Theatre Sarah Bernhardt in which Mme. Schwob plays the hero-troubadour.

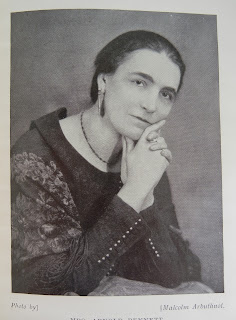

Marguerite Moreno (1871–1948) born Lucie Marie Marguerite Monceau was a French stage and film actress. The French writer Marcel Schwob, who was madly in love with her, wrote in 1895: "I am at Marguerite Moréno's complete disposal. She is allowed to do everything she wants with me and that includes killing me".

Schwob ill and very pale and extremely gloomy and depressed. neither of them could eat and each grumbled at the other for not eating. Before dinner Schwob had described to me the fearful depression of spirit accompanied by inability to work, which has held him for several months. Every morning he got up feeling, "Well, another day and I can do nothing, I have nothing to look forward to, no future." And, speaking of my novel, "Leonora", he said: "You have got hold of the greatest of all themes, the agony of the older geberation in watching the rise of the younger." Yet he is probably not 40. In talking of Kipling's literary power, he said that an artist could not do as he liked with his imagination; it would not stand improper treatment, undue fatigue etc. in youth; and that a man who wrote many short stories early in life was bound to decay prematurely. He said that he himself was going through this experience.