Chores and a moderate walk this morning. Got some ideas for my next "Books & Persons" article which will be about autumn books. Everywhere has that autumnal feel now. I was reflecting on how the loss of daylight has its effect on our mood. Somebody should do a study about it.

This afternoon to a remarkable art exhibition of the work of Kathe Kollwitz. I had no idea who she was but had been told that her work was exceptional - and it was. She is the same age as me and East Prussian by birth though she has lived most of her life in a poor working class district of Berlin. Her theme is social justice, for the poor, for workers, and for women. Her work is largely lithographs and woodcuts, suitable for printing. For purposes of propaganda I expect.

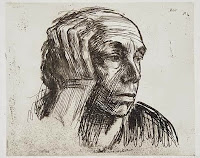

About a third of the exhibits are self-portraits, the earliest dating from when she was about thirty to the recent past. She portrays herself as a strong, serious, rather resigned (I think) figure. I was set to wondering about what an artist has in mind when doing a self-portrait. Are they aiming for verisimilitude, or attempting to convey a message? Depends on the artist of course. Certainly for Kollwitz I felt she was searching for a sort of generic womanhood, using her own features merely as a foundation. I only saw one photograph of Kollwitz herself at the exhibition and though she looked serious, I don't think she would have been easily recognisable from the self-portraits.

About a third of the exhibits are self-portraits, the earliest dating from when she was about thirty to the recent past. She portrays herself as a strong, serious, rather resigned (I think) figure. I was set to wondering about what an artist has in mind when doing a self-portrait. Are they aiming for verisimilitude, or attempting to convey a message? Depends on the artist of course. Certainly for Kollwitz I felt she was searching for a sort of generic womanhood, using her own features merely as a foundation. I only saw one photograph of Kollwitz herself at the exhibition and though she looked serious, I don't think she would have been easily recognisable from the self-portraits.

No comments:

Post a Comment