Wednesday, November 4th., London.

Came to London yesterday morning. The Atkinses arrived on Saturday and left on Monday. An impression of off-season, half-emptiness throughout West End. Girls driving motor cars. If one thinks about recruiting one soon gets obsessed by number of young men about the streets. Lunch with Pinker at Arts Club. "Price of Love" had sold 6,700 Engl. and 3,500 colonial. Season good, at shops; but libraries 'obstructive' as Pinker said.

|

| Dr. Walter Hines Page |

He had seen Conrad that morning, just returned from Austrian Poland. C. had no opinion of Russian army, and had come to England to influence public opinion to get good terms for Austria! As if he could. Pinker had also seen Henry James, who often goes to see Page, American Ambassador, in afternoons. They have long quiet talks together. First time H.J. opened his heart to Page, he stopped and said: "But, I oughtn't to talk like this to you, a neutral." Said Page: "My dear man, if you knew how it does me good to hear it!" Hy. James is strongly pro-English, and comes to weeping point sometimes.

Then tea at A.B.C. Shop opposite Charing Cross. Down into smoking room. A few gloomy and rather nice men. One couple of men deliberately attacking dish of hot tea-cakes. Terrible. Familiar smell of hot tea. A.B.C shops are still for me one of the most characteristic things in London.

A.B.C. (the Aerated Bread Company) was revolutionary for its chain of self-service A.B.C. tea shops, the fast-food outlets of their day. These grew from A.B.C. opening the U.K.'s first tearoom in 1864, two years after the company's founding. The first A.B.C. tea shop opened in the courtyard of London's Fenchurch Street Railway Station. The idea for opening the tearoom is attributed to a London-based manageress of the Aerated Bread Company "who'd been serving gratis tea and snacks to customers of all classes, [and] got permission to put a commercial public tearoom on the premises." The motivation for the company acting upon the manageress's suggestion was "the fact that the sale of bread alone was not proving a dividend-earning proposition." The tearooms were significant since they provided one of the first public places where women in the Victorian era could eat a meal, by herself or with women friends, without a male escort. While by 1880 unescorted women could visit higher-end restaurants, they had to avoid the bar. As safe havens for unescorted women of the Victorian era, the A.B.C. tea shops were recommended to delegates of the Congress of the International Council of Women held in London the week ending 9 July 1899. At its peak in 1923, A.B.C. had 150 branch shops in London and 250 tea shops and was second in terms of outlets only to J. Lyons and Co. This proliferation led George Orwell to view A.B.C.'s tea shops, and those of its competitors, as :

"the sinister strand in English catering, the relentless industrialisation that was overtaking it: the 162 teashops of the Aerated Bread Company, the

Lyons Corner Houses, which rolled out 10 miles of swiss roll every day and manufactured millions of “frood” (frozen cooked food) meals, the milk bars that served "no real food at all … Everything comes out of a carton or a tin, or is hauled out of a refrigerator or squirted out of a tap or squeezed out of a tube."

"Milestones" on buses again. Same servants at hotels and clubs.

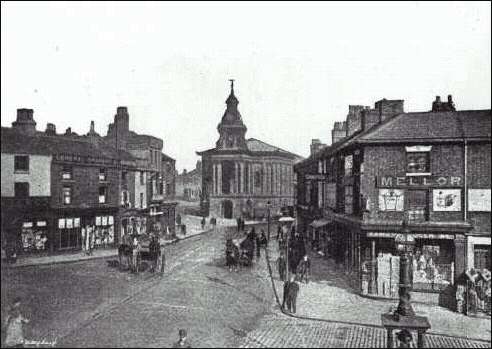

After tea to N.L.C. but I saw nobody I knew. Then, through latest dusk, to Reform, where Rickards and I dined. London not so dark as I expected, owing to lamps in centre of roads throwing down a volume of light in the shape of a lamp shade (they are blackened at top). After dinner, Ponting's antarctic cinema, followed by poor war pictures, at Phil. Hall.

Provincial-seeming audience. Woman behind me continually exclaimed under her breath, with a sharp, low intake of breath, 'Oh', 'Oh'.

|

| Reform Club |

Two nice old johnnies at Reform Club, phlegmy-voiced, one fat, one thin, quoting latin to each other over their reading. One said he had a music professor from Liege coming to stay with him - seemed rather naively proud of it. Many old men at Reform. Their human-ness, almost boyishness, comes out. Lying placards on evening papers. P.M.G. "Great German Retreat" on strength of a phrase in Belgian communique affecting one small part of battle line only.