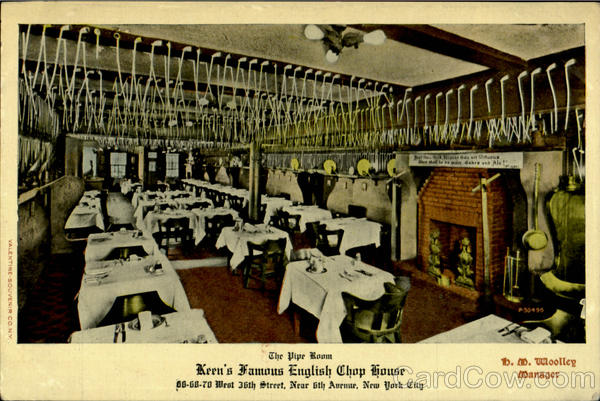

| Martha Brandes in L'Escalade |

Welcome to our blog!

It's better than a bat in the eye with a burnt stick!

This blog makes liberal use of AB's journals, letters, travel notes, and other sources.

And make sure to visit The Arnold Bennett Society for expert information and comment on all aspects of the life and work of AB.

Thursday, 30 November 2017

Not skating

Wednesday, November 30th., Rue de Calais, Paris.

I met Emile Martin by appointment at the Palais de Glace, Champs Elysee, yesterday. A large circular place: curiously ghostly effect of the electric light on the powdery surface of the ice. Apparently the site used to be the setting for occasional bullfights, and was remodelled for this new recreation in 1890. My first visit. It is now evidently the resort of high class cocottes, rastas, and rich wastrels. Some of the women were excessively chic. I enjoyed observing them.

I met Emile Martin by appointment at the Palais de Glace, Champs Elysee, yesterday. A large circular place: curiously ghostly effect of the electric light on the powdery surface of the ice. Apparently the site used to be the setting for occasional bullfights, and was remodelled for this new recreation in 1890. My first visit. It is now evidently the resort of high class cocottes, rastas, and rich wastrels. Some of the women were excessively chic. I enjoyed observing them.

I spent most of the day yesterday searching for an idea to take the concert chapter of my novel "Sacred and Profane Love" forward. I found it towards evening. Then I went to "L'Escalade" by Maurice Donnay, at the Renaissance. This is quite a minor piece with insufficient material, and what material there is not too well arranged. It is surprising to me how a man like Donnay could let such a work go out of the manufactory. Guitry and Brandes were magnificent, full of distinction; Guitry's son had also his father's distinction. It must be a source of grave anxiety to fathers how their sons will turn out. Especially if the father is himself distinguished. How often I have noticed that sons who take up the same career as their father prove to be lesser figures.

Wednesday, 29 November 2017

Middle age lament

Wednesday, November 29th., Comarques, Thorpe-le-Soken.

I have hardly done any work since I came back from Dublin in September. Quite why, I don't know. I still seem to be busy, but not the sort of busyness that brings in money. Marguerite is spending at a good rate, especially on clothes. I feel a bit discontented, out of sorts, in need of a change. But no change in prospect. Of course I have now reached the age of fifty which is something of a milestone, and it is getting dark so early, and feel I would be happier were I single again. A middle-aged man's lament.

I have been reading Swinnerton's "Nocturne". Good. Perhaps very good. Only a short novel and all set in the course of a few hours, with only five characters. No plot as such, Swinnerton's intention being to 'get inside' the heads of his characters. And he succeeds pretty well. The setting is a 'respectable' working class home somewhere in London where live two sisters and their father who is more or less helpless, needing constant care. Both sisters are desperate for love and for some sort of escape from their dreary existence. Jenny, the younger, is a romantic, sharply intelligent, unpredictable, a dreamer. Emmy, the elder, is conventional, unimaginative, caring, with a deep reservoir of love for the right man if she can find him. By the end, Emmy is on the road to happiness, whilst Jenny looks likely to continue to be dissatisfied.

I have been reading Swinnerton's "Nocturne". Good. Perhaps very good. Only a short novel and all set in the course of a few hours, with only five characters. No plot as such, Swinnerton's intention being to 'get inside' the heads of his characters. And he succeeds pretty well. The setting is a 'respectable' working class home somewhere in London where live two sisters and their father who is more or less helpless, needing constant care. Both sisters are desperate for love and for some sort of escape from their dreary existence. Jenny, the younger, is a romantic, sharply intelligent, unpredictable, a dreamer. Emmy, the elder, is conventional, unimaginative, caring, with a deep reservoir of love for the right man if she can find him. By the end, Emmy is on the road to happiness, whilst Jenny looks likely to continue to be dissatisfied.

I can't quite decide whether this would have been better edited to become a short story, or extended to a normal size novel. Probably the latter had I been dealing with it. There is very little back story which could, I think, have been introduced to advantage. There is also very little description of the sisters' home. I could have made a lot of that. Swinnerton is excellent in describing a visit to a music hall, and could have done more to flesh out the context of the sisters' lives. Also, we get privileged access to the characters thoughts but not so much about how their thoughts and emotions express themselves in nuances of behaviour; the sort of thing that Conrad is a master of. I enjoyed the read. It could reasonably be described as a tour de force, and I think it will sell well.

In the Telegraph today was a letter from Lord Lansdowne calling for a re-think on the possibility of a negotiated peace with Germany. A brave gesture by a man who has been Foreign Secretary, and therefore should be heeded. But I have no doubt that there will be a predictable response tomorrow, with the word 'traitor' to the fore. Essentially Lansdowne argues that the allies should restate their war aims in an attempt to bring about peace before the prolongation of the war leads to the ruin of the civilized world. I agree completely, but I have no intention of saying so in public. If pressed I shall be non-commital.

In the Telegraph today was a letter from Lord Lansdowne calling for a re-think on the possibility of a negotiated peace with Germany. A brave gesture by a man who has been Foreign Secretary, and therefore should be heeded. But I have no doubt that there will be a predictable response tomorrow, with the word 'traitor' to the fore. Essentially Lansdowne argues that the allies should restate their war aims in an attempt to bring about peace before the prolongation of the war leads to the ruin of the civilized world. I agree completely, but I have no intention of saying so in public. If pressed I shall be non-commital.

I have hardly done any work since I came back from Dublin in September. Quite why, I don't know. I still seem to be busy, but not the sort of busyness that brings in money. Marguerite is spending at a good rate, especially on clothes. I feel a bit discontented, out of sorts, in need of a change. But no change in prospect. Of course I have now reached the age of fifty which is something of a milestone, and it is getting dark so early, and feel I would be happier were I single again. A middle-aged man's lament.

I can't quite decide whether this would have been better edited to become a short story, or extended to a normal size novel. Probably the latter had I been dealing with it. There is very little back story which could, I think, have been introduced to advantage. There is also very little description of the sisters' home. I could have made a lot of that. Swinnerton is excellent in describing a visit to a music hall, and could have done more to flesh out the context of the sisters' lives. Also, we get privileged access to the characters thoughts but not so much about how their thoughts and emotions express themselves in nuances of behaviour; the sort of thing that Conrad is a master of. I enjoyed the read. It could reasonably be described as a tour de force, and I think it will sell well.

In the Telegraph today was a letter from Lord Lansdowne calling for a re-think on the possibility of a negotiated peace with Germany. A brave gesture by a man who has been Foreign Secretary, and therefore should be heeded. But I have no doubt that there will be a predictable response tomorrow, with the word 'traitor' to the fore. Essentially Lansdowne argues that the allies should restate their war aims in an attempt to bring about peace before the prolongation of the war leads to the ruin of the civilized world. I agree completely, but I have no intention of saying so in public. If pressed I shall be non-commital.

In the Telegraph today was a letter from Lord Lansdowne calling for a re-think on the possibility of a negotiated peace with Germany. A brave gesture by a man who has been Foreign Secretary, and therefore should be heeded. But I have no doubt that there will be a predictable response tomorrow, with the word 'traitor' to the fore. Essentially Lansdowne argues that the allies should restate their war aims in an attempt to bring about peace before the prolongation of the war leads to the ruin of the civilized world. I agree completely, but I have no intention of saying so in public. If pressed I shall be non-commital.

Tuesday, 28 November 2017

War news

Saturday, November 28th., Comarques, Thorpe-le-Soken.

I met Colonel Tabor (of Cyclists) in the road yesterday. He said that the War Office was apparently taking quite seriously the danger of a raid. He said that many officers were now having a few days leave, and that one had breakfasted in the trenches and dined at his club in London. I imagine that is apocryphal but it does bring home the bizarre situation that there is a war going on just over the horizon. I think it is only a matter of time before someone in the south east claims to have heard the guns firing. On Thursday 700 sailors were killed when HMS Bulwark blew up in the harbour at Sheerness, Kent. How many more will die before this is all over I wonder?

The Colchester road is being mined just east of the point where the Tendring road branches off. Four or six soldiers digging holes on either side of the road (4 in all) about 4 feet cube. The bridge next to the railway station is also being mined. Twelve engineers in the village and more to come.

I had run out of book space and have had some new shelves made for a particular wall in my study, to my own design. Spent some time last evening arranging the books. Inevitably I became involved in reading and lost all track of time. At one point I was browsing in my set of "The Yellow Book" and unexpectedly came upon my own story "A Letter Home" in Volume VI. I read it with genuine pleasure.

I met Colonel Tabor (of Cyclists) in the road yesterday. He said that the War Office was apparently taking quite seriously the danger of a raid. He said that many officers were now having a few days leave, and that one had breakfasted in the trenches and dined at his club in London. I imagine that is apocryphal but it does bring home the bizarre situation that there is a war going on just over the horizon. I think it is only a matter of time before someone in the south east claims to have heard the guns firing. On Thursday 700 sailors were killed when HMS Bulwark blew up in the harbour at Sheerness, Kent. How many more will die before this is all over I wonder?

The Colchester road is being mined just east of the point where the Tendring road branches off. Four or six soldiers digging holes on either side of the road (4 in all) about 4 feet cube. The bridge next to the railway station is also being mined. Twelve engineers in the village and more to come.

I had run out of book space and have had some new shelves made for a particular wall in my study, to my own design. Spent some time last evening arranging the books. Inevitably I became involved in reading and lost all track of time. At one point I was browsing in my set of "The Yellow Book" and unexpectedly came upon my own story "A Letter Home" in Volume VI. I read it with genuine pleasure.

Monday, 27 November 2017

Theatre things

Sunday, November 27th., Cadogan Square, London.

We lunched at Norman Wilkinson's. He lives alone at Strawberry House, Chiswick Mall. Very nice and tasteful. Several old harpsichords and similar instruments, in perfect order, on which he plays nicely. He is charming, sensible and has taste. A pleasure to spend time with an 'old school' sort. So different from some of the flashy stage types one is forced into company with. I am inclined to think that if it were not for Dorothy's continuing infatuation with all things theatre I might put it all behind me. Feeling a bit dissatisfied with life generally - probably presages some digestive disorder. I don't seem to have much time for myself. Busier than ever but not doing things I particularly want to do. Of course I have free will and could decline some invitations but one becomes involved in a social round and I have to think about Dorothy as well as myself. I envy Wilkinson who seems to lead a life of quiet contentment. But perhaps he envies me. Strange world!

We dined at the Ivy, and saw there the St. John Ervines, Hutchinsons, Lytton Strachey, the Basil Deans, etc., etc.Then to the first night of the Sitwell entertainment, "First Class Passengers Only", at the Arts Theatre Club. Packed. Some part amusing. More parts tedious. Some fine acting. Some rotten. It was a sort of Revue in backchat.

"Mr. Prohack" starring Charles Laughton seems to be doing well at the Court. Better than I expected at least.

| Strawberry House |

We dined at the Ivy, and saw there the St. John Ervines, Hutchinsons, Lytton Strachey, the Basil Deans, etc., etc.Then to the first night of the Sitwell entertainment, "First Class Passengers Only", at the Arts Theatre Club. Packed. Some part amusing. More parts tedious. Some fine acting. Some rotten. It was a sort of Revue in backchat.

"Mr. Prohack" starring Charles Laughton seems to be doing well at the Court. Better than I expected at least.

Saturday, 25 November 2017

Literary exchange

Saturday, November 25th., Villa des Nefliers.

I am engaged in an exchange by letter with Edward Garnett, reviewer for the Nation. His recent review of "The Old Wives' Tale" was as good as I could wish for but I took exception to his throwaway remark that in previous books I "frittered myself away in pleasing the fourth-rate tastes of Philistia". Insufferable elitism! So what if I write some books that have a more 'popular' audience in mind? No doubt they lack Garnett's sophisticated taste, but they are readers too and why should I not, as a professional author, address them? As long as I write as well as I can it seems to me not to matter much if not everything is great literature. He also seemed to imply that my only effective subject is The Five Towns.

I asked him if he had read "A Great Man" or "Buried Alive", both of which are set elsewhere and are by no means fourth rate. In fairness he replied to say that he may have overdone the 'Philistia' business. He had in mind "The Grand Babylon Hotel". Admittedly that is a lark, but it is a well written lark. He says he has reviewed "A Great Man" but has not read "Buried Alive". I also mentioned "Whom God Hath Joined" which I still consider to be under-rated .

I don't know why this sort of thing gets under my skin. The high-brows do cause me to see red. Might there be an element of provincial inferiority complex?

I am engaged in an exchange by letter with Edward Garnett, reviewer for the Nation. His recent review of "The Old Wives' Tale" was as good as I could wish for but I took exception to his throwaway remark that in previous books I "frittered myself away in pleasing the fourth-rate tastes of Philistia". Insufferable elitism! So what if I write some books that have a more 'popular' audience in mind? No doubt they lack Garnett's sophisticated taste, but they are readers too and why should I not, as a professional author, address them? As long as I write as well as I can it seems to me not to matter much if not everything is great literature. He also seemed to imply that my only effective subject is The Five Towns.

I asked him if he had read "A Great Man" or "Buried Alive", both of which are set elsewhere and are by no means fourth rate. In fairness he replied to say that he may have overdone the 'Philistia' business. He had in mind "The Grand Babylon Hotel". Admittedly that is a lark, but it is a well written lark. He says he has reviewed "A Great Man" but has not read "Buried Alive". I also mentioned "Whom God Hath Joined" which I still consider to be under-rated .

I don't know why this sort of thing gets under my skin. The high-brows do cause me to see red. Might there be an element of provincial inferiority complex?

Friday, 24 November 2017

Getting about

Thursday, November 24th., Cadogan Square, London.

Chores this morning after some letter writing. I had some trouble concentrating as my mind kept turning to the unemployed miners who arrived in London yesterday having walked 180 miles from the Rhondda Valley. Baldwin refused to meet them. Later there was a rally in Trafalgar Square - they marched to the Square carrying lighted lamps, knapsacks and mugs, and supported by brass and fife bands. I wish had had been there to see it. Apparently Arthur Cook, Secretary of the Miners' Federation, told them that "unless the government faces up to the problem of unemployment, a revolutionary situation will be created in this country which no leader will be able to withstand." Strong words for strong men but unlikely to move Baldwin who has probably never seen a mine. I don't suppose anything will come of it. The people in this country are too docile and well fed.

Chores this morning after some letter writing. I had some trouble concentrating as my mind kept turning to the unemployed miners who arrived in London yesterday having walked 180 miles from the Rhondda Valley. Baldwin refused to meet them. Later there was a rally in Trafalgar Square - they marched to the Square carrying lighted lamps, knapsacks and mugs, and supported by brass and fife bands. I wish had had been there to see it. Apparently Arthur Cook, Secretary of the Miners' Federation, told them that "unless the government faces up to the problem of unemployment, a revolutionary situation will be created in this country which no leader will be able to withstand." Strong words for strong men but unlikely to move Baldwin who has probably never seen a mine. I don't suppose anything will come of it. The people in this country are too docile and well fed.

This afternoon I took D. to the Guildhall Art Gallery which had been recommended to me. Mainly Victorian paintings but some good quality works. I was particularly struck by John Collier's "Clytemnestra". In fact I kept going back to look at it again. Highly dramatic. Tells the whole story in one unforgettable image. Collier has made her look proud, immensely strong and slightly deranged all at the same time. Blood dripping off the axe is a nice touch. And behind her is a mysterious light which draws the observer into the murder room in imagination. You feel as if Agamemnon is lying there, just out of your sight. Worth the visit just for that as far as I was concerned. D. was less impressed than me.

This afternoon I took D. to the Guildhall Art Gallery which had been recommended to me. Mainly Victorian paintings but some good quality works. I was particularly struck by John Collier's "Clytemnestra". In fact I kept going back to look at it again. Highly dramatic. Tells the whole story in one unforgettable image. Collier has made her look proud, immensely strong and slightly deranged all at the same time. Blood dripping off the axe is a nice touch. And behind her is a mysterious light which draws the observer into the murder room in imagination. You feel as if Agamemnon is lying there, just out of your sight. Worth the visit just for that as far as I was concerned. D. was less impressed than me.

Went to the Savoy this evening for "The Other Club" dinner in the Pinafore Room. 15 minutes late which is regarded as rather bad form. Alfred Mason in the chair. I sat near to Lutyens, Jos Wedgwood, Hamar Greenwood, Birkenhead, William Berry and Anthony Hope. I had some sparring with Birkenhead, rather loud and abusive, but good natured. However, I could be just as abusive as he could. It was Birkenhead (F.E. Smith as he was then) who founded the club with Churchill. They put it about that it was because the old clubs would not accept them. Too brash. I don't believe it myself - they are both arch self-publicists. Supposed to be a limit on the number of politician members, but it seems to have been forgotten. I should have asked Birkenhead if he had spoken at the rally. He would have had apoplexy.

|

| Lord Birkenhead |

Thursday, 23 November 2017

Dark clouds

Monday, November 23rd., Comarques, Thorpe-le-Soken.

Sisters Campion dined here Saturday. They explained that there were only 60 soldiers at Frinton, and that they had a tremendous lot done for them in the way of entertainment and comforts. They said however, disapprovingly, that after quitting the social club at night - cocoa etc. - the men could go to their canteen and get drunk. Seemed surprised by this revelation of men's character. There is a continuing sense of unreality about the war. I wonder how long 'entertainment and comforts' will be maintained? Fewer people are saying: "It will be all over by Christmas". In fact I don't think I have heard anybody say it recently. News that the Germans are advancing rapidly east into Poland as well. They are a formidable enemy and I fear that things will get worse before they get better.

I was almost laid up with a liver attack this weekend. Possibly a reaction in part to my trip to the Potteries. No more news about my mother. I don't think it can be much longer.

We were at Mrs. Tollinton's in Tendring for tea. Cold upstairs room with bedroom grate - a bedroom used as a secondary drawing room. I got near the morsel of fire. Mrs. Tollinton mere, a widow with cap. The wife's sister in black, with a nervous habit of shrugging her shoulders as if in amiable protest or agreement with a protest. or a humorous comment. Though there wasn't much humour abroad. Tollinton himself a very learned man who has this year published "Clement of Alexandria: A Study in Christian Liberalism". I am told that the work deals with Clement, his times and contemporaries; with his views on Paganism, Marriage, and Property; on the Logos, the Incarnation, and Gnosticism; on the Church, the Sacraments, and the Scriptures. I am glad to say that I was not asked for any opinion on it, nor even if I had read it at all. Probably the assumption was made that the answer would be negative in either case.

Sisters Campion dined here Saturday. They explained that there were only 60 soldiers at Frinton, and that they had a tremendous lot done for them in the way of entertainment and comforts. They said however, disapprovingly, that after quitting the social club at night - cocoa etc. - the men could go to their canteen and get drunk. Seemed surprised by this revelation of men's character. There is a continuing sense of unreality about the war. I wonder how long 'entertainment and comforts' will be maintained? Fewer people are saying: "It will be all over by Christmas". In fact I don't think I have heard anybody say it recently. News that the Germans are advancing rapidly east into Poland as well. They are a formidable enemy and I fear that things will get worse before they get better.

I was almost laid up with a liver attack this weekend. Possibly a reaction in part to my trip to the Potteries. No more news about my mother. I don't think it can be much longer.

We were at Mrs. Tollinton's in Tendring for tea. Cold upstairs room with bedroom grate - a bedroom used as a secondary drawing room. I got near the morsel of fire. Mrs. Tollinton mere, a widow with cap. The wife's sister in black, with a nervous habit of shrugging her shoulders as if in amiable protest or agreement with a protest. or a humorous comment. Though there wasn't much humour abroad. Tollinton himself a very learned man who has this year published "Clement of Alexandria: A Study in Christian Liberalism". I am told that the work deals with Clement, his times and contemporaries; with his views on Paganism, Marriage, and Property; on the Logos, the Incarnation, and Gnosticism; on the Church, the Sacraments, and the Scriptures. I am glad to say that I was not asked for any opinion on it, nor even if I had read it at all. Probably the assumption was made that the answer would be negative in either case.

Wednesday, 22 November 2017

Forest sounds

Tuesday, November 22nd., Les Sablons, near Moret.

Yesterday I finished the second act of "An Angel Unawares". The third will be very easy to do. So today I began to plan out in detail the first part of "Sacred and Profane Love". The first part is going to be entirely magnificent. I outlined the plot to Davray. I don't think he was very struck by it, and he asked whether the British public would stand it. I think he has the idea that the British will be shocked by the heroine 'giving' herself to the pianist, whereas the French would, of course, take it in their stride. However from a crude outline he had nothing upon which to judge.

Yesterday I finished the second act of "An Angel Unawares". The third will be very easy to do. So today I began to plan out in detail the first part of "Sacred and Profane Love". The first part is going to be entirely magnificent. I outlined the plot to Davray. I don't think he was very struck by it, and he asked whether the British public would stand it. I think he has the idea that the British will be shocked by the heroine 'giving' herself to the pianist, whereas the French would, of course, take it in their stride. However from a crude outline he had nothing upon which to judge.

I walked all about Moret this morning, and got somewhat lost in the forest this afternoon. Then I read Swinburne.

I noticed in the forest yesterday afternoon that the noise of the wind in the branches was indeed like the noise of the sea; but always distant; the noise never seemed to be near me. I got lost once and took one path after another aimlessly until it occurred to me to steer by the sun. The moonrise was magnificent, and the weather became frosty. I noticed how large the moon seemed, just having risen. Why should it look bigger when it is low in the sky compared to near the zenith? It is the same distance away.

After leaving Davray's at 10 o'clock I went as far as the forest again, but the diverging avenues of trees did not produce the effect I had hoped for; there was too much gloom.

Yesterday I finished the second act of "An Angel Unawares". The third will be very easy to do. So today I began to plan out in detail the first part of "Sacred and Profane Love". The first part is going to be entirely magnificent. I outlined the plot to Davray. I don't think he was very struck by it, and he asked whether the British public would stand it. I think he has the idea that the British will be shocked by the heroine 'giving' herself to the pianist, whereas the French would, of course, take it in their stride. However from a crude outline he had nothing upon which to judge.

Yesterday I finished the second act of "An Angel Unawares". The third will be very easy to do. So today I began to plan out in detail the first part of "Sacred and Profane Love". The first part is going to be entirely magnificent. I outlined the plot to Davray. I don't think he was very struck by it, and he asked whether the British public would stand it. I think he has the idea that the British will be shocked by the heroine 'giving' herself to the pianist, whereas the French would, of course, take it in their stride. However from a crude outline he had nothing upon which to judge.I walked all about Moret this morning, and got somewhat lost in the forest this afternoon. Then I read Swinburne.

I noticed in the forest yesterday afternoon that the noise of the wind in the branches was indeed like the noise of the sea; but always distant; the noise never seemed to be near me. I got lost once and took one path after another aimlessly until it occurred to me to steer by the sun. The moonrise was magnificent, and the weather became frosty. I noticed how large the moon seemed, just having risen. Why should it look bigger when it is low in the sky compared to near the zenith? It is the same distance away.

After leaving Davray's at 10 o'clock I went as far as the forest again, but the diverging avenues of trees did not produce the effect I had hoped for; there was too much gloom.

Tuesday, 21 November 2017

Interesting people

Wednesday, November 21st., Cadogan Square, London.

First night of Quintero's play "100 Years Old" at Hammersmith. Lovely 1st. Act. Other acts not so good. I have a feeling that it is not going to be a success.

Then Dorothy, Sissie, Tertia and I went to Dorothy Warren's and Philip Trotter's pre-nuptial supper at Boulestin's. About 200 I should think. Mainly Bloomsbury high-brows of course. I sat next to Lady Raleigh, and opposite the betrothed couple. Anna May Wong and Howard Baker there also. I must say that Anna May Wong is rather excitingly exotic. Apparently she has come to Europe because she was restricted to minor acting parts in Hollywood; a sort of unofficial colour bar. She hopes to do better here . I think she will. The only question really is whether the film people can capture her effortless sensuality. I hope to see more of her.

I was talking to James B. who I first met at the ministry. He's not there now. He is vrey interested in archaeology, and particularly the Romans. His idea is that there is a lot more Roman remains waiting to be discovered in this country. The thing is that most places which were Roman population centres are now built-up and so the remains are buried. He makes a point of frequenting sites where building work is going on in the hope of discoveries. So far, not very much. He has the idea that the original site of London, which the Romans called Londinium, would have had an amphitheatre and he is trying to work out where it would have been. Maybe somewhere near the Guildhall in the City is his best guess, but I don't think they will let him dig up the Guildhall on the off-chance of archaeological finds.

First night of Quintero's play "100 Years Old" at Hammersmith. Lovely 1st. Act. Other acts not so good. I have a feeling that it is not going to be a success.

|

| Anna May Wong |

I was talking to James B. who I first met at the ministry. He's not there now. He is vrey interested in archaeology, and particularly the Romans. His idea is that there is a lot more Roman remains waiting to be discovered in this country. The thing is that most places which were Roman population centres are now built-up and so the remains are buried. He makes a point of frequenting sites where building work is going on in the hope of discoveries. So far, not very much. He has the idea that the original site of London, which the Romans called Londinium, would have had an amphitheatre and he is trying to work out where it would have been. Maybe somewhere near the Guildhall in the City is his best guess, but I don't think they will let him dig up the Guildhall on the off-chance of archaeological finds.

Sunday, 19 November 2017

A sick-room visit

Thursday, November 19th., Comarques, Thorpe-le-Soken.

On Wednesday afternoon I went to Burslem to see my mother who is reported to be past hope. I saw her at 8 p.m. and remained alone with her for about half an hour. She looked very small, especially her head in the hollow of the pillows. The outlines of her face very sharp; hectic cheeks; breathed with her mouth open, and much rumour of breath in her body; her nose seemed more hooked. Had, in fact, become hooked. Scanty hair. She had a very weak self-pitying voice, but with sudden birsts of strong voice, imperative and flinging out of arms. She still had a great deal of strength. She forgot most times in the middle of a sentence, and it took her a long time to recall.

She was very glad to see me and held my hand all the time under the bedclothes. She spoke of the most trifling things as if tremendously important. She was seldom fully conscious and often dozed and then woke up with a start. She had no pain but often muttered in anguish: "What am I to do? What am I to do?". Amid tossed bedclothes you could see numbers on corners of blankets. On medicine table siphon, saucer, spoon, large soap-dish, brass flower bowl (empty). The gas (very bad burner) screened by a contraption of Family Bible, some wooden thing, and a newspaper. It wasn't level. She had it altered. Said it annoyed her terribly. Gas stove burning. Temperature barely 60. Damp chill penetrating my legs. The clock had a very light, delicate, striking sound. Trams and buses did not disturb her though sometimes they made talking difficult.

Round-topped panels of wardrobe. She wanted to be satisfied that her purse was on a particular tray of the wardrobe. Apparently she has arterial sclerosis and patchy congestion of the lungs. Her condition was very distressing (though less so than my father's when he lay dying), and it seemed strange to me that this should necessarily be the end of life, that a life couldn't always end more easily. Well of course it could if a sane approach to these things was adopted, but we remain at the mercy of the religious powers who argue that life is a 'gift' and to take it ourselves is a 'sin'. What poppycock! I know what a proud woman my mother was and how she would have hated to find herself in this pitiful state. If I had more courage I might have smothered her with a pillow. I thought of doing so, but held back. I had a sort of waking dream or fantasy of being in a courtroom defending my actions in the most eloquent way and becoming thereby a sort of popular hero. Embarrassing to think of it.

I went in again at 11.45 p.m. She was asleep, breathing noisily. Nurse, in black, installed for the night. Sometimes a bright smile appeared on my mother's face but it went in an instant. She asked for her false teeth, and she wanted her ears syringed again so that she could hear better. She was easier in the morning after a good night, but certainly weaker. Mouth closed and eyes shut tight. Lifting of chin right up to get head in line with body for breathing. A bad sign.

On Wednesday afternoon I went to Burslem to see my mother who is reported to be past hope. I saw her at 8 p.m. and remained alone with her for about half an hour. She looked very small, especially her head in the hollow of the pillows. The outlines of her face very sharp; hectic cheeks; breathed with her mouth open, and much rumour of breath in her body; her nose seemed more hooked. Had, in fact, become hooked. Scanty hair. She had a very weak self-pitying voice, but with sudden birsts of strong voice, imperative and flinging out of arms. She still had a great deal of strength. She forgot most times in the middle of a sentence, and it took her a long time to recall.

She was very glad to see me and held my hand all the time under the bedclothes. She spoke of the most trifling things as if tremendously important. She was seldom fully conscious and often dozed and then woke up with a start. She had no pain but often muttered in anguish: "What am I to do? What am I to do?". Amid tossed bedclothes you could see numbers on corners of blankets. On medicine table siphon, saucer, spoon, large soap-dish, brass flower bowl (empty). The gas (very bad burner) screened by a contraption of Family Bible, some wooden thing, and a newspaper. It wasn't level. She had it altered. Said it annoyed her terribly. Gas stove burning. Temperature barely 60. Damp chill penetrating my legs. The clock had a very light, delicate, striking sound. Trams and buses did not disturb her though sometimes they made talking difficult.

Round-topped panels of wardrobe. She wanted to be satisfied that her purse was on a particular tray of the wardrobe. Apparently she has arterial sclerosis and patchy congestion of the lungs. Her condition was very distressing (though less so than my father's when he lay dying), and it seemed strange to me that this should necessarily be the end of life, that a life couldn't always end more easily. Well of course it could if a sane approach to these things was adopted, but we remain at the mercy of the religious powers who argue that life is a 'gift' and to take it ourselves is a 'sin'. What poppycock! I know what a proud woman my mother was and how she would have hated to find herself in this pitiful state. If I had more courage I might have smothered her with a pillow. I thought of doing so, but held back. I had a sort of waking dream or fantasy of being in a courtroom defending my actions in the most eloquent way and becoming thereby a sort of popular hero. Embarrassing to think of it.

I went in again at 11.45 p.m. She was asleep, breathing noisily. Nurse, in black, installed for the night. Sometimes a bright smile appeared on my mother's face but it went in an instant. She asked for her false teeth, and she wanted her ears syringed again so that she could hear better. She was easier in the morning after a good night, but certainly weaker. Mouth closed and eyes shut tight. Lifting of chin right up to get head in line with body for breathing. A bad sign.

Saturday, 18 November 2017

Old times

Friday, November 19th., Villa des Nefliers.

Yesterday I finished making a list of all social, political and artistic events which I thought possibly useful for my novel between 1872 and 1882. Tedious bore for a trifling ultimate result in the book. But necessary. Not so much the facts that are important, but getting into the period. I feel it is important to write as if I am there. In fact it is the only way I can write with authenticity. The period just overlaps my own school days of course and I sense that there will be a lot of me in the book. Whilst walking in the forest today I practically arranged most of the construction of the first part of the novel. Still lacking a title for it. If I thought an ironic title would do, I would call it "A Thoughtful Young Man". But the public is so damned slow on the uptake.

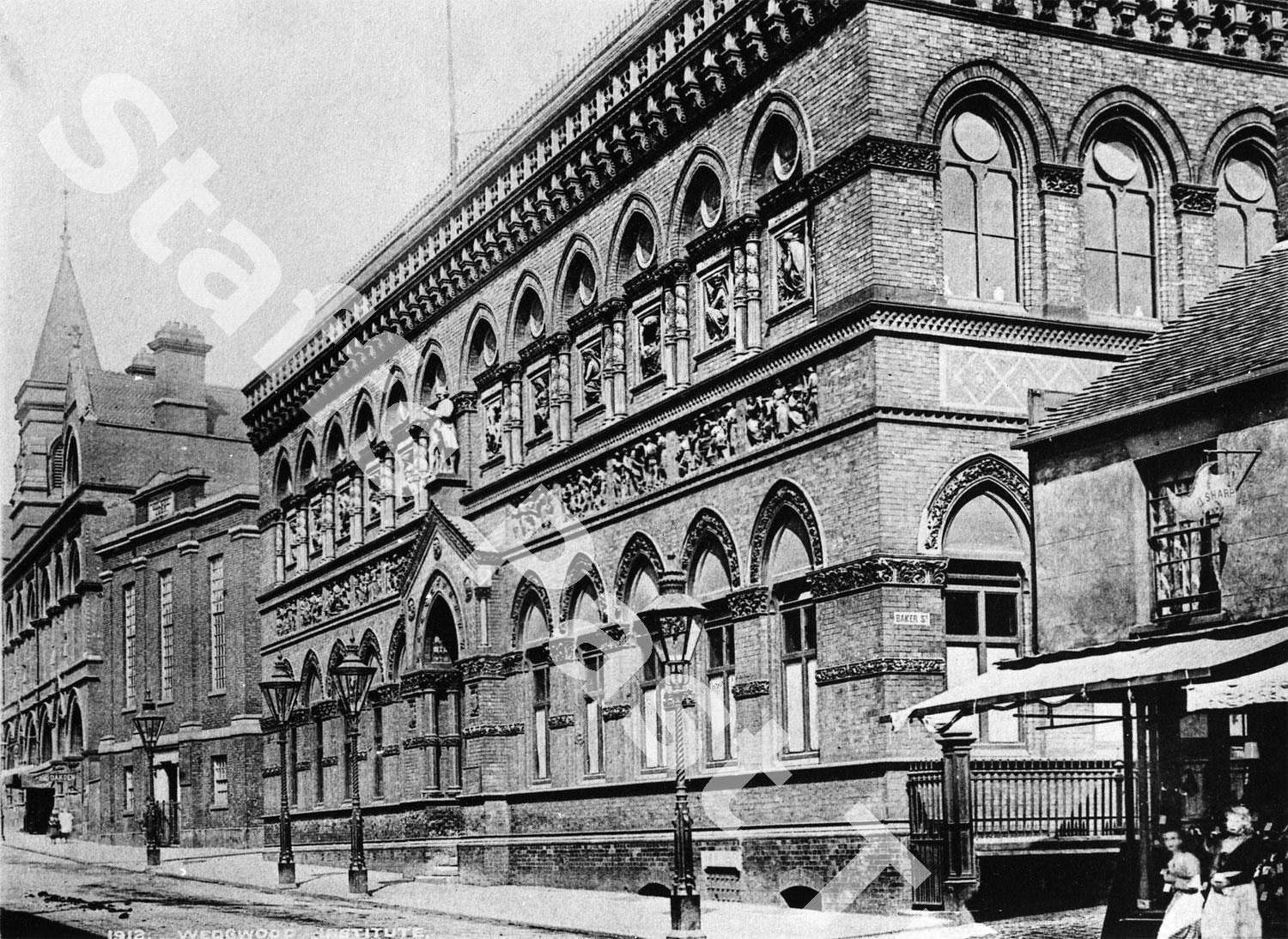

Talking of schooldays I have had a card from a Mr R.W. Wright asking about my 'career' at the Middle School. I had no career! No idea why he wants to know. I can't quite get clear in my head whether I left either late in 1883 or early in 1884. I think I was there 3 or 4 years. I came from the Burslem Endowed School. I went into the Lower Sixth and rose to the Upper Sixth soon afterwards, and in due course I was Head Boy. I passed no outside examinations while at the school. I played left wing forward in the football team, but no match cricket. I must have been less than mediocre at sports. Mr. Hurley, who is a linguist of international reputation, coached me afterwards in German for the London Matric, which I passed almost immediately. My mother will know the school dates and I shall be seeing her soon in the Potteries.

I am getting to the end of my year's work. In a week I shall have nothing to do except the collection, on the spot, of more information for the novel. Perhaps I will come upon a title.

Today I finished, and mounted, another water colour, of Arbonne - one of my least rotten.

Yesterday I finished making a list of all social, political and artistic events which I thought possibly useful for my novel between 1872 and 1882. Tedious bore for a trifling ultimate result in the book. But necessary. Not so much the facts that are important, but getting into the period. I feel it is important to write as if I am there. In fact it is the only way I can write with authenticity. The period just overlaps my own school days of course and I sense that there will be a lot of me in the book. Whilst walking in the forest today I practically arranged most of the construction of the first part of the novel. Still lacking a title for it. If I thought an ironic title would do, I would call it "A Thoughtful Young Man". But the public is so damned slow on the uptake.

|

| Wedgwood Institute containing Burslem Endowed School |

I am getting to the end of my year's work. In a week I shall have nothing to do except the collection, on the spot, of more information for the novel. Perhaps I will come upon a title.

Today I finished, and mounted, another water colour, of Arbonne - one of my least rotten.

Friday, 17 November 2017

In good form

Friday, November 17th., Eltham, Torquay.

Presently staying with the Phillpotts's for a few days. I have a large bedroom with a prime view over Torbay. Always relaxing here but I am working as well. I feel in great form for work. In fact I feel pretty well in general at the moment. The new bachelor lifestyle suits me well. Yesterday I took Mrs. P. out shopping and we became a little flirtatious, being about the same age. Nothing serious of course but it does the spirit good to be able to make a sort of proto-sexual connection; I thought I had lost the knack of it! And of course there is Adelaide, the daughter, late 20s I should think. Quite pretty and I think she has a preference for older men. Interesting that this sort of thing is going around in my head nowadays.

Dorothy has a small part at the Kingsway Theatre, but she couldn't really have come here with me anyway. Some proprieties must be observed. For some reason we got onto talking about Ruskin last evening and Eden rehearsed the old story about his unconsummated marriage with Effie Gray. Allegedly he was completely unmanned at the sight of her naked body, or more specifically her pubic hair. I must say that I think it apocryphal. More likely in my view that he was a suppressed homosexual, married for reasons of convention an undeveloped young woman, and just couldn't do the necessary when it came to it. One wonders how these stories arise and are propagated. If I have time and opportunity I will try to find out some facts.

Dorothy was trying to advise me about treatment for my stammer the other evening. Nice of her to make the effort but, as I said to her, I think I have considered or indeed tried all possible therapies. Any treatment will do you a certain amount of good for a time, because the affection is extremely responsive to hetero-suggestion. But none that I have ever heard of will act when it is really needed. I used to discuss this matter with the late W.H.R. Rivers, one of the greatest specialists in nervous affections. He could never suggest anything better than to forget the trouble and leave it alone. As he stammered himself he would be likely to know all there was to be known. Also he was a very intimate friend of mine and a really great man. The affection is due to a defect of the brain, which gives contradictory orders simultaneously when disturbed in a certain way. I have even tried hypnotism. Why the subject is not more readily studied than it is by experts I have never understood for the affection is very widespread (among males - it is very rare among females). The nervous strain of it is of course continuous and severe - very severe. The said strain is too much for many sufferers and they retire to the completest privacy that they can arrange for. It is always a marvel to me that I, with my aciute general sensitiveness, have risen above this enormous handicap and am even, inspite of it, recognised as a great 'persuader' of people.

Presently staying with the Phillpotts's for a few days. I have a large bedroom with a prime view over Torbay. Always relaxing here but I am working as well. I feel in great form for work. In fact I feel pretty well in general at the moment. The new bachelor lifestyle suits me well. Yesterday I took Mrs. P. out shopping and we became a little flirtatious, being about the same age. Nothing serious of course but it does the spirit good to be able to make a sort of proto-sexual connection; I thought I had lost the knack of it! And of course there is Adelaide, the daughter, late 20s I should think. Quite pretty and I think she has a preference for older men. Interesting that this sort of thing is going around in my head nowadays.

Dorothy has a small part at the Kingsway Theatre, but she couldn't really have come here with me anyway. Some proprieties must be observed. For some reason we got onto talking about Ruskin last evening and Eden rehearsed the old story about his unconsummated marriage with Effie Gray. Allegedly he was completely unmanned at the sight of her naked body, or more specifically her pubic hair. I must say that I think it apocryphal. More likely in my view that he was a suppressed homosexual, married for reasons of convention an undeveloped young woman, and just couldn't do the necessary when it came to it. One wonders how these stories arise and are propagated. If I have time and opportunity I will try to find out some facts.

Dorothy was trying to advise me about treatment for my stammer the other evening. Nice of her to make the effort but, as I said to her, I think I have considered or indeed tried all possible therapies. Any treatment will do you a certain amount of good for a time, because the affection is extremely responsive to hetero-suggestion. But none that I have ever heard of will act when it is really needed. I used to discuss this matter with the late W.H.R. Rivers, one of the greatest specialists in nervous affections. He could never suggest anything better than to forget the trouble and leave it alone. As he stammered himself he would be likely to know all there was to be known. Also he was a very intimate friend of mine and a really great man. The affection is due to a defect of the brain, which gives contradictory orders simultaneously when disturbed in a certain way. I have even tried hypnotism. Why the subject is not more readily studied than it is by experts I have never understood for the affection is very widespread (among males - it is very rare among females). The nervous strain of it is of course continuous and severe - very severe. The said strain is too much for many sufferers and they retire to the completest privacy that they can arrange for. It is always a marvel to me that I, with my aciute general sensitiveness, have risen above this enormous handicap and am even, inspite of it, recognised as a great 'persuader' of people.

Wednesday, 15 November 2017

A few ideas

Monday, November 15th., Cadogan Square, London.

Duff Tayler and I lunched together yesterday and discussed his sick leg, and the future of the Lyric, Hammersmith. Duff (Alistair) is a short agreeable Scotsman of means, devoted to the theatre. He has relied on my support in his battles with Playfair. He has an idea for burlesquely producing one of the old melodramas, such as "Sweeny Todd". So we walked at once to French's and bought six old melodramas, of which we each took three. I drove home, slept, and read "Sweeny Todd" and "Black-eyed Susan". I decided "Sweeny" would do but "B.E.Susan" would not. Eliozabeth L. came ot dinner and we took her to the first night of "The Would-be Gentleman" at the Lyric. This was rather less awful than I had feared: but it was pretty amateurish, and the recommendations of Duff and myself had not been carried out with any thoroughness. Anstey appeared and looked charming, and aged, and naif. He looked far younger at rehearsals. Dorothy did not care for the production, nor did Tertia. Elizabeth did, but Elizabeth is not discriminating.

Today I finished an interesting book called "The Man in the High Castle". The author's name is P. Dick, an American. There were four things I liked about it. Firstly, it is an 'alternative history', which I always find interesting. Not only that but there is an alternative history (a book) within the alternative history - clever idea and well executed. Secondly the characters are well-drawn and all are conflicted in their lives. Authentic. Thirdly, the plot is gripping, and I was keen to keep reading to find out what would happen. Always a good sign. Finally, running through the novel is a sort of philosophical strand relating to the Chinese I Ching. Clearly this is something of real importance for Dick. The whole novel was imbued with a sort of dark fatalism. The ending was strange and a bit disappointing, but it has left me thinking. It may do well if properly promoted.

Duff Tayler and I lunched together yesterday and discussed his sick leg, and the future of the Lyric, Hammersmith. Duff (Alistair) is a short agreeable Scotsman of means, devoted to the theatre. He has relied on my support in his battles with Playfair. He has an idea for burlesquely producing one of the old melodramas, such as "Sweeny Todd". So we walked at once to French's and bought six old melodramas, of which we each took three. I drove home, slept, and read "Sweeny Todd" and "Black-eyed Susan". I decided "Sweeny" would do but "B.E.Susan" would not. Eliozabeth L. came ot dinner and we took her to the first night of "The Would-be Gentleman" at the Lyric. This was rather less awful than I had feared: but it was pretty amateurish, and the recommendations of Duff and myself had not been carried out with any thoroughness. Anstey appeared and looked charming, and aged, and naif. He looked far younger at rehearsals. Dorothy did not care for the production, nor did Tertia. Elizabeth did, but Elizabeth is not discriminating.

Today I finished an interesting book called "The Man in the High Castle". The author's name is P. Dick, an American. There were four things I liked about it. Firstly, it is an 'alternative history', which I always find interesting. Not only that but there is an alternative history (a book) within the alternative history - clever idea and well executed. Secondly the characters are well-drawn and all are conflicted in their lives. Authentic. Thirdly, the plot is gripping, and I was keen to keep reading to find out what would happen. Always a good sign. Finally, running through the novel is a sort of philosophical strand relating to the Chinese I Ching. Clearly this is something of real importance for Dick. The whole novel was imbued with a sort of dark fatalism. The ending was strange and a bit disappointing, but it has left me thinking. It may do well if properly promoted.

Tuesday, 14 November 2017

A day in Paris

Monday, November 14th., 4, Rue de Calais, Paris.

I spent the whole of yesterday en ville. I went to Ullman's Sunday morning reception at his studio, and found some magnificent pictures, and much praise of my books. I particularly enjoyed a watercolour, in muted tones, of a river scene; just the sort of thing I would like to produce myself, but far in advance of my ability. Ullman is an American but lives more or less permanently in Paris. Ten years younger than me but already gaining a significant reputation. He is a very versatile artist - portraits, landscapes, figurative and impressionist. I expect he is not really appreciated in America.

I spent the whole of yesterday en ville. I went to Ullman's Sunday morning reception at his studio, and found some magnificent pictures, and much praise of my books. I particularly enjoyed a watercolour, in muted tones, of a river scene; just the sort of thing I would like to produce myself, but far in advance of my ability. Ullman is an American but lives more or less permanently in Paris. Ten years younger than me but already gaining a significant reputation. He is a very versatile artist - portraits, landscapes, figurative and impressionist. I expect he is not really appreciated in America.

At 6 o'clock I left. I went to the Cafe D'Orsay, and had a vermouth-cassis, and then I walked all the way by the Seine to Schwob's. He was alone and the chinese servant had been ill and looked sickly. Moreno was away on tour. We were intensely glad to see each other and shook hands with both left and right hands. He was much better and his interest in books had revived. Books were all over the place and he had got a lot of new ones. Ting watched over us while we dined, and Schwob gave me the history of his transactions as to plays with David Belasco. Then he asked if I cared to go out as the carriage was at his disposal. The carriage proved to be a magnificent De Dion cab, and I suppose it belongs to Moreno. We whirled off to La Scala. It was hot and crowded.

At 6 o'clock I left. I went to the Cafe D'Orsay, and had a vermouth-cassis, and then I walked all the way by the Seine to Schwob's. He was alone and the chinese servant had been ill and looked sickly. Moreno was away on tour. We were intensely glad to see each other and shook hands with both left and right hands. He was much better and his interest in books had revived. Books were all over the place and he had got a lot of new ones. Ting watched over us while we dined, and Schwob gave me the history of his transactions as to plays with David Belasco. Then he asked if I cared to go out as the carriage was at his disposal. The carriage proved to be a magnificent De Dion cab, and I suppose it belongs to Moreno. We whirled off to La Scala. It was hot and crowded.

Schwob said that he enjoyed music halls and frequented them, and he certainly enjoyed this. Some of the items were very good. He has the habit, which one finds in all sorts of people, of mildly but constantly insisting that a thing is good, as if to convince himself. If I began by saying that a thing was not good, he at once agreed. His taste, though extremely fine, is capricious; it is at the mercy of his feelings.

Schwob said that he enjoyed music halls and frequented them, and he certainly enjoyed this. Some of the items were very good. He has the habit, which one finds in all sorts of people, of mildly but constantly insisting that a thing is good, as if to convince himself. If I began by saying that a thing was not good, he at once agreed. His taste, though extremely fine, is capricious; it is at the mercy of his feelings.

He whirled me home in about two minutes. I tremendously enjoyed the evening. He was absolutely charming, and his English is so good and sure, and he looked so plaintive and in need of moral support, with his small figure and his pale face, and his loose clothes, and his hat that is always too large for him. Yet I don't know anyone who could be more independent and pugnacious, morally, than Schwob. I have never seen him so, but I know that he would be so if occasion arose.

At 6 o'clock I left. I went to the Cafe D'Orsay, and had a vermouth-cassis, and then I walked all the way by the Seine to Schwob's. He was alone and the chinese servant had been ill and looked sickly. Moreno was away on tour. We were intensely glad to see each other and shook hands with both left and right hands. He was much better and his interest in books had revived. Books were all over the place and he had got a lot of new ones. Ting watched over us while we dined, and Schwob gave me the history of his transactions as to plays with David Belasco. Then he asked if I cared to go out as the carriage was at his disposal. The carriage proved to be a magnificent De Dion cab, and I suppose it belongs to Moreno. We whirled off to La Scala. It was hot and crowded.

At 6 o'clock I left. I went to the Cafe D'Orsay, and had a vermouth-cassis, and then I walked all the way by the Seine to Schwob's. He was alone and the chinese servant had been ill and looked sickly. Moreno was away on tour. We were intensely glad to see each other and shook hands with both left and right hands. He was much better and his interest in books had revived. Books were all over the place and he had got a lot of new ones. Ting watched over us while we dined, and Schwob gave me the history of his transactions as to plays with David Belasco. Then he asked if I cared to go out as the carriage was at his disposal. The carriage proved to be a magnificent De Dion cab, and I suppose it belongs to Moreno. We whirled off to La Scala. It was hot and crowded. Schwob said that he enjoyed music halls and frequented them, and he certainly enjoyed this. Some of the items were very good. He has the habit, which one finds in all sorts of people, of mildly but constantly insisting that a thing is good, as if to convince himself. If I began by saying that a thing was not good, he at once agreed. His taste, though extremely fine, is capricious; it is at the mercy of his feelings.

Schwob said that he enjoyed music halls and frequented them, and he certainly enjoyed this. Some of the items were very good. He has the habit, which one finds in all sorts of people, of mildly but constantly insisting that a thing is good, as if to convince himself. If I began by saying that a thing was not good, he at once agreed. His taste, though extremely fine, is capricious; it is at the mercy of his feelings.He whirled me home in about two minutes. I tremendously enjoyed the evening. He was absolutely charming, and his English is so good and sure, and he looked so plaintive and in need of moral support, with his small figure and his pale face, and his loose clothes, and his hat that is always too large for him. Yet I don't know anyone who could be more independent and pugnacious, morally, than Schwob. I have never seen him so, but I know that he would be so if occasion arose.

Monday, 13 November 2017

Going out

Saturday, November 13th., Cadogan Square, London.

Gale, rainy windy showers early.

I drove in driving rain to the Tate Gallery, in order to think over my novel, and saw some good English pictures. There are indeed some fine ones. The elder of the two Tate lecturers was very good on both Blake and Rossetti. He pointed out the humour in Rossetti's watercolours, and he very well explained their origin. Then I wrote some more notes for my novel - to be called, pro tem., "Accident". Also I found names for two of the characters. Interesting that I use the word 'found', because that is what it feels like. As if the names have been lying around, just waiting for me to come across them. I suppose they have in a way, somewhere in my head.

I drove in driving rain to the Tate Gallery, in order to think over my novel, and saw some good English pictures. There are indeed some fine ones. The elder of the two Tate lecturers was very good on both Blake and Rossetti. He pointed out the humour in Rossetti's watercolours, and he very well explained their origin. Then I wrote some more notes for my novel - to be called, pro tem., "Accident". Also I found names for two of the characters. Interesting that I use the word 'found', because that is what it feels like. As if the names have been lying around, just waiting for me to come across them. I suppose they have in a way, somewhere in my head.

We drove, still in the rain - or had the rain just stopped? - to the Lyceum for the first night of the Russian ballet. The whole high-brow and snob world was there, with a good sprinkling of decent people. The spectacle was good. I liked "Petrouschka" as much as ever, and "The House Party" more than ever. I begin now to understand the latter. It is all Sodom and Gomorrah. "The Swan Lake" had much applause: a fine old-fashioned example of Petipa's work. Orchestra better than usual.

Gale, rainy windy showers early.

We drove, still in the rain - or had the rain just stopped? - to the Lyceum for the first night of the Russian ballet. The whole high-brow and snob world was there, with a good sprinkling of decent people. The spectacle was good. I liked "Petrouschka" as much as ever, and "The House Party" more than ever. I begin now to understand the latter. It is all Sodom and Gomorrah. "The Swan Lake" had much applause: a fine old-fashioned example of Petipa's work. Orchestra better than usual.

Sunday, 12 November 2017

Currents of imagination

Friday, November 12th., Villa des Nefliers.

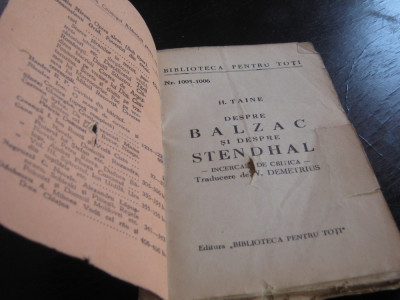

Taine's long essay (over 100 pp.) on Balzac, is really very good reading, especially when he comes to describe the big characters, such as Joseph Bridau, Grandet, and the Baron Hulot. Lying awake last night, after a fearful crash caused by the faience suspension falling out of the ceiling in the hall, I had the desire to do likewise for one or two English novelists. It is Taine's method that appeals to me, and the intoxicating effectf a vast number of short sentences or clauses hurled down one after the other. Funny how ideas come to one in the night and make one feel excited, and a whole edifice of imagination is built up. Then, back to sleep, and in the cold light of morning the realisation that it was all so much poppycock. What profit would there be for me, a professional writer in literary biographies? Who would buy them? I can imagine writing a newspaper column about books and writers, but nothing more 'academic' - too busy making a living.

Taine's long essay (over 100 pp.) on Balzac, is really very good reading, especially when he comes to describe the big characters, such as Joseph Bridau, Grandet, and the Baron Hulot. Lying awake last night, after a fearful crash caused by the faience suspension falling out of the ceiling in the hall, I had the desire to do likewise for one or two English novelists. It is Taine's method that appeals to me, and the intoxicating effectf a vast number of short sentences or clauses hurled down one after the other. Funny how ideas come to one in the night and make one feel excited, and a whole edifice of imagination is built up. Then, back to sleep, and in the cold light of morning the realisation that it was all so much poppycock. What profit would there be for me, a professional writer in literary biographies? Who would buy them? I can imagine writing a newspaper column about books and writers, but nothing more 'academic' - too busy making a living.

Night thoughts are strange phenomena though and I probably have more than most as I rarely sleep through a night. A few days ago I went to bed very tired having walked 9 or 10 miles during the day and slept from 11 pm to 6 am. I was amazed. That must be the longest continual period of sleep I have experienced for years. Sometimes, after waking, I rise, do what is necessary, and then go more or less straight back to sleep. But more often I am awake for a while, or rather in that sort of intermediate stage between wakefulness and sleep. That is when the odd night thoughts occur. Often worrying about something, or rehearsing an impending meeting, or turning over a problem. Occasionally erotic, but not often. I have learned from experience not to fight it. If I try to make myself sleep I invariably fail. Best just to drift away on the currents of imagination.

Taine's long essay (over 100 pp.) on Balzac, is really very good reading, especially when he comes to describe the big characters, such as Joseph Bridau, Grandet, and the Baron Hulot. Lying awake last night, after a fearful crash caused by the faience suspension falling out of the ceiling in the hall, I had the desire to do likewise for one or two English novelists. It is Taine's method that appeals to me, and the intoxicating effectf a vast number of short sentences or clauses hurled down one after the other. Funny how ideas come to one in the night and make one feel excited, and a whole edifice of imagination is built up. Then, back to sleep, and in the cold light of morning the realisation that it was all so much poppycock. What profit would there be for me, a professional writer in literary biographies? Who would buy them? I can imagine writing a newspaper column about books and writers, but nothing more 'academic' - too busy making a living.

Taine's long essay (over 100 pp.) on Balzac, is really very good reading, especially when he comes to describe the big characters, such as Joseph Bridau, Grandet, and the Baron Hulot. Lying awake last night, after a fearful crash caused by the faience suspension falling out of the ceiling in the hall, I had the desire to do likewise for one or two English novelists. It is Taine's method that appeals to me, and the intoxicating effectf a vast number of short sentences or clauses hurled down one after the other. Funny how ideas come to one in the night and make one feel excited, and a whole edifice of imagination is built up. Then, back to sleep, and in the cold light of morning the realisation that it was all so much poppycock. What profit would there be for me, a professional writer in literary biographies? Who would buy them? I can imagine writing a newspaper column about books and writers, but nothing more 'academic' - too busy making a living.Night thoughts are strange phenomena though and I probably have more than most as I rarely sleep through a night. A few days ago I went to bed very tired having walked 9 or 10 miles during the day and slept from 11 pm to 6 am. I was amazed. That must be the longest continual period of sleep I have experienced for years. Sometimes, after waking, I rise, do what is necessary, and then go more or less straight back to sleep. But more often I am awake for a while, or rather in that sort of intermediate stage between wakefulness and sleep. That is when the odd night thoughts occur. Often worrying about something, or rehearsing an impending meeting, or turning over a problem. Occasionally erotic, but not often. I have learned from experience not to fight it. If I try to make myself sleep I invariably fail. Best just to drift away on the currents of imagination.

Saturday, 11 November 2017

Charming

Saturday, November 11th., Cadogan Square, London.

I have made a decent start to my new novel "Imperial Palace". It will be 150,000 words long, and not divided into parts. I think I have now grown out of dividing novels into parts. Today such a division strikes me as being a bit pompous. I know the main plot but by no means all the incidents thereof, though I have a few titbits of episodes which I shall not omit.

An amusing titbit came my way recently, but I do not intend to use it in the novel. A youngish Canadian ex-soldier had become interested in a charming blonde English girl who served in some capacity in a country house where a friend of mine was staying. So interested that he offered to give her a day's jaunt in London. She accepted. They went. "First Class and everything." Return tickets. In the First Class carriage was a small boy travelling alone. The child cried all the time. The charming blonde took no notice whatever of the child, made no attempt to sympathise with him in any way. The Canadian waited and waited for her to behave to the forlorn child as a kind-hearted woman should. In vain. At Waterloo he said laconaically to the charmer: "here's your return ticket." And walked off and left her. He could not stand a woman like that, be she ever so charming!

I have made a decent start to my new novel "Imperial Palace". It will be 150,000 words long, and not divided into parts. I think I have now grown out of dividing novels into parts. Today such a division strikes me as being a bit pompous. I know the main plot but by no means all the incidents thereof, though I have a few titbits of episodes which I shall not omit.

An amusing titbit came my way recently, but I do not intend to use it in the novel. A youngish Canadian ex-soldier had become interested in a charming blonde English girl who served in some capacity in a country house where a friend of mine was staying. So interested that he offered to give her a day's jaunt in London. She accepted. They went. "First Class and everything." Return tickets. In the First Class carriage was a small boy travelling alone. The child cried all the time. The charming blonde took no notice whatever of the child, made no attempt to sympathise with him in any way. The Canadian waited and waited for her to behave to the forlorn child as a kind-hearted woman should. In vain. At Waterloo he said laconaically to the charmer: "here's your return ticket." And walked off and left her. He could not stand a woman like that, be she ever so charming!

Friday, 10 November 2017

No gushing

Friday, November 10th., Fulham Park Gardens, London.

After cogitating off and on all through the night I decided upon what will probably be the first sentence of my "Anna Tellwright" novel: "Bursley, the ancient home of the potter, has an antiquity of a thousand years" - and also upon the arrangement of the first long paragraph describing the Potteries. Now that I have a beginning, I am confident that by steady application I can make my novel a good one.

This evening, at his request, I called to 'have a chat' with Cyril Maude at the Haymarket Theatre. I saw him in his dressing room, a small place with the walls all sketched over by popular artists. Round the room was a dado border of prints of Nicholson's animal drawings. Although the curtain would not rise for over half an hour Maude was made-up and dressed. he was very kind and good natured about my one-act play, "The Stepmother", without overflowing into that gush which nearly all actors give off on all occasions of politeness. He said that he and Harrison would certainly consider seriously any 3 or 4 act play of mine. He advised me against doing any more curtain raisers. He seems genuinely interested in my work which is a great encouragement.

After cogitating off and on all through the night I decided upon what will probably be the first sentence of my "Anna Tellwright" novel: "Bursley, the ancient home of the potter, has an antiquity of a thousand years" - and also upon the arrangement of the first long paragraph describing the Potteries. Now that I have a beginning, I am confident that by steady application I can make my novel a good one.

|

| Cyril Maude |

Clerical connections

Friday, November 10th., Mulberry Gardens, Hampshire.

A rather pleasant autumnal day in Hampshire. Sunny for the most part. Leisurely breakfast, and then off to Salisbury which I had thought was in Hampshire but is in fact in Wiltshire. Dominated of course by the great spire of the cathedral which seems incongruously tall from a distance but strangely fitting the body of the structure from nearby. The cathedral close is extensive, green, and surrounded by an eclectic mix of substantial houses. Mostly grace and favour homes for the clergy I would imagine - the trials of being a cleric!

One of the buildings on the close has been converted into a museum and has benefitted greatly from the legacy of the noted archaeologist Augustus Pitt-Rivers. The latter had estates in Wiltshire and was an indefatigable excavator and collector. His scientific approach to excavation has had a major impact on archaeology. Many of his finds are on display - pots, copper items, stone tools, human skulls ....... Fascinating.

Strolled out this afternoon. There seem to be a great many rivers and streams locally. In fact it is rather wet, though my informants claim that rainfall is moderate, and speak appreciatively about the good local weather. On a bridle path I startled a middle aged man who had stopped to consult a pocket book. As people often do who are surprised in this way he felt the need to explain himself, and soon disclosed that he was a Baptist minister out visiting his 'flock'. A little pasty, thinning hair, a bit unhealthy looking, but with the broad smile which churchmen seem to feel it incumbent upon them to offer to strangers. He seemed a little disappointed when I indicated that I was only visiting - perhaps hoped for a new recruit! What continually surprises me is how ready most people are to talk about themselves, but how rarely they show any interest in their interlocutor. He soon told me that he was married, had two children, had lived in the area all his life, and liked to get away from his desk as often as he could, though he clearly wanted me to understand that he was very busy. He showed no interest in me whatsoever. Let's hope he does better with his flock.

A rather pleasant autumnal day in Hampshire. Sunny for the most part. Leisurely breakfast, and then off to Salisbury which I had thought was in Hampshire but is in fact in Wiltshire. Dominated of course by the great spire of the cathedral which seems incongruously tall from a distance but strangely fitting the body of the structure from nearby. The cathedral close is extensive, green, and surrounded by an eclectic mix of substantial houses. Mostly grace and favour homes for the clergy I would imagine - the trials of being a cleric!

One of the buildings on the close has been converted into a museum and has benefitted greatly from the legacy of the noted archaeologist Augustus Pitt-Rivers. The latter had estates in Wiltshire and was an indefatigable excavator and collector. His scientific approach to excavation has had a major impact on archaeology. Many of his finds are on display - pots, copper items, stone tools, human skulls ....... Fascinating.

Strolled out this afternoon. There seem to be a great many rivers and streams locally. In fact it is rather wet, though my informants claim that rainfall is moderate, and speak appreciatively about the good local weather. On a bridle path I startled a middle aged man who had stopped to consult a pocket book. As people often do who are surprised in this way he felt the need to explain himself, and soon disclosed that he was a Baptist minister out visiting his 'flock'. A little pasty, thinning hair, a bit unhealthy looking, but with the broad smile which churchmen seem to feel it incumbent upon them to offer to strangers. He seemed a little disappointed when I indicated that I was only visiting - perhaps hoped for a new recruit! What continually surprises me is how ready most people are to talk about themselves, but how rarely they show any interest in their interlocutor. He soon told me that he was married, had two children, had lived in the area all his life, and liked to get away from his desk as often as he could, though he clearly wanted me to understand that he was very busy. He showed no interest in me whatsoever. Let's hope he does better with his flock.

Thursday, 9 November 2017

War news

Tuesday, November 10th., Comarques, Thorpe-le-Soken.

Alcock came. He is the Chief Customs Officer of Newhaven and Tilbury. Once, having observed my style of walking, he referred to it as : "Bennett's quarter-deck manner." Nice phrase, and I wasn't at all put out, in fact, quite pleased. Today he told us a lot about transport work which is obviously going to change enormously now that we are at war. He said Newhaven port had a huge sealed envelope of orders to be executed on receipt of coded telegrams. When the first telegram came the orders proved to be dated 1911. This was rather good. The orders, as I heard them, seemed excellent.

We hear that the German cruiser Emden has finally been destroyed. She has done much damage in the East and has kept nearly the whole of Admiral Jerram's fleet in search of her. She was finally run down by HMS Sydney at Cocos Island yesterday.

Alcock came. He is the Chief Customs Officer of Newhaven and Tilbury. Once, having observed my style of walking, he referred to it as : "Bennett's quarter-deck manner." Nice phrase, and I wasn't at all put out, in fact, quite pleased. Today he told us a lot about transport work which is obviously going to change enormously now that we are at war. He said Newhaven port had a huge sealed envelope of orders to be executed on receipt of coded telegrams. When the first telegram came the orders proved to be dated 1911. This was rather good. The orders, as I heard them, seemed excellent.

We hear that the German cruiser Emden has finally been destroyed. She has done much damage in the East and has kept nearly the whole of Admiral Jerram's fleet in search of her. She was finally run down by HMS Sydney at Cocos Island yesterday.

Wednesday, 8 November 2017

False start

Sunday, November 8th., 6 Victoria Grove, London.

Dr. Farrar said that the difficulties of diagnosis were much greater than most people imagined. As an instance he stated that in certain cases it was impossible for a doctor to say whether a patient was suffering from consumption or typhoid fever, widely and essentially different though these two diseases were. He told me of the case of a girl he had been called to attend in a 'house of business'. She had a persistently high temperature and eventually was admitted to St. George's Hospital. At length, after a fortnight, just as they were about to put her on an ordinary diet, she was taken with diarrhoea, haemorrhage of the bowels, and other unmistakable symptoms of typhoid fever. He didn't say whether others at her 'workplace' had been affected.

Farrar has become a friend, as well as being my medical advisor. I owe him a significant debt of gratitude. When I first saw him in Putney I had no real career in prospect, but envied those around me who were engrossed in their careers as artists, musicians and journalists. Farrar, after giving me a physical overhaul, administered a mental tonic that had the summary effect of stimulating my self-esteem. He said, sitting back with his stethoscope round his neck and his fingers steepled: "You know, you're one of the most highly strung men I've ever met." I realised that my temperament was that of an artist, in tune with those around me, fine-grained, sensitive, and gifted. It made me take stock of myself and, as it were, re-launch myself after a false start.

Dr. Farrar said that the difficulties of diagnosis were much greater than most people imagined. As an instance he stated that in certain cases it was impossible for a doctor to say whether a patient was suffering from consumption or typhoid fever, widely and essentially different though these two diseases were. He told me of the case of a girl he had been called to attend in a 'house of business'. She had a persistently high temperature and eventually was admitted to St. George's Hospital. At length, after a fortnight, just as they were about to put her on an ordinary diet, she was taken with diarrhoea, haemorrhage of the bowels, and other unmistakable symptoms of typhoid fever. He didn't say whether others at her 'workplace' had been affected.